Jane Austen would have turned 250. Here's why she is still relevant

Few writers have made a greater mark than Jane Austen.

Austen's six novels - including Emma and Pride and Prejudice - were groundbreaking in the early 1800s.

As a pioneer of free indirect style and the marriage plot, her mastery has inspired many homages and imitations — both on the page and the screen — over the last two centuries.

On the 250th anniversary of her birthday, we look back at Austen's life and legacy.

A portrait of Jane Austen based on a drawing by her sister Cassandra.

Public domain

Who was Jane Austen?

Austen was born on December 16, 1775, in the village of Steventon in rural Hampshire, where her father, the Reverend George Austen, was a clergyman.

Her mother, Cassandra, was "known for her poems and her wit", Devoney Looser, who is a professor of English at Arizona State University, tells ABC Radio National's The Book Show.

"She had two very interesting parents, but they were not by any means a family of great wealth."

Jane Austen fans pose at at Winchester Cathedral with a Bank of England £10 note featuring the author's portrait.

AFP

The Austens were what's often described as lower gentry: people of 'good birth' who weren't landowners themselves.

The Austen home was an "intellectual environment" but one in which money was tight.

To supplement the family's income, George Austen took in a series of male students, to the ultimate benefit of his daughter's education.

"There were, one scholar has estimated, 19 different boys who spent some years of their lives in this clergyman Reverend George Austen's home," Looser says.

"In effect, Jane Austen didn't just grow up as a clergyman's daughter; she grew up in a boys' school."

Early signs of genius

Austen is believed to have started writing when she was 11. She made copies of some of these early works, written between 1787 and 1798, later published as her juvenilia.

Looser says that while many critics initially dismissed this early writing as lightweight, it is now viewed more favourably.

"You can see her brilliance, her genius in these works from 11, 12, 13 years old. It's quite incredible."

Her early work often played on sending up the literary conventions of the day to comic effect.

"The juvenilia is filled with drunkenness, adultery, murder - not the things you necessarily associate with the mature Jane Austen, the Jane Austen of the six major novels," Looser says.

Devoney Looser is a professor of English at Arizona State University and the author of Wild for Austen: A Rebellious, Subversive and Untamed Jane.

Supplied

The collected works of Jane Austen

Aspiring authors, take heart: Austen's first attempts to have her work published were unsuccessful.

One of Austen's novels (no one is sure which) that her father submitted to a publisher in the 1790s was rejected sight unseen.

In 1803, she sold a manuscript for £10 ($NZ30) to a publisher, who, for reasons unknown, refused to either publish the novel or return it to her.

(Her brother eventually acquired the novel back in 1816, and it was published as Northanger Abbey in 1817).

While Austen was a prolific writer, she had to wait until she was 35 to see her first novel in print.

Sense and Sensibility, published in 1811, was a reworking of her first full-length novel, Elinor and Marianne, written years earlier. No copies of the earlier manuscript survive.

Jennifer Ehle as Elizabeth Bennet and Colin Firth as Fitzwilliam Darcy in the 1995 drama series Pride and Prejudice.

BBC

In 1813, Austen published her next novel, Pride and Prejudice — also based on an early draft, known as First Impressions, that she began in 1797, when she was 21.

She published two more novels in her lifetime: Mansfield Park (1814) and Emma (1816).

Another two novels — Northanger Abbey and Persuasion — were published after her death in July 1817.

Austen published her novels anonymously and was relatively little-known during her lifetime, but news of her true identity soon began to spread thanks to the likes of the Prince Regent (later King George IV), who was "a notorious gossip".

"Once the Prince Regent knows your identity, you can assume that the cat's out of the bag," Looser says.

The woman behind the books

To the great disappointment of Austen fans and biographers alike, most of her letters were destroyed after her death, some by her sister Cassandra and others by her niece Fanny. Only 160 of her missives remain.

The first published biography of the author, written by her brother Henry just months after her death, presented Austen as a saintly and, it must be said, dull figure.

"He says that her life was not a life of event. This is obviously not true," Looser says.

"We can tell from her letters that she was not someone who was boring and nice and faultless. She had a rapier wit, and she wasn't afraid to use it, especially in private."

Camille Rutherford and Pablo Pauly in the 2024 French comedy Jane Austen Wrecked My Life.

supplied

Looser makes a case against Austen's perceived mildness in her 2025 book Wild for Austen: A Rebellious, Subversive and Untamed Jane.

While Austen wasn't an out-and-out radical, she broke with social convention in her efforts to become a published author.

"Certainly, she was not the wildest person of her day, but there were things that she was doing that were really outside of what was proper. They were outside of what was conventionally feminine," Looser says.

"The ideal woman was supposed to be passive and quiet, and not unlike what Henry Austin describes in his biographical notice of her in 1818.

"This is clearly not who Jane Austen was."

Looking for clues in her novels

Many have turned to her writing to learn more about who the elusive Austen really was.

"Clearly, she has a sense of what it means to be good, and her characters who do good and behave in ways that are good have better ends," Looser says.

What differentiates Austen from her contemporaries is the way she dispenses justice in her novels.

"She goes a little light on her villains," Looser says. "She's responding to a very strong didactic moralising tradition in her era that kills off the villain or sends them away … They die a tragic death because they're bad. She doesn't do that.

"She lets her most flawed and villainous characters have a different kind of bad end. Often, they're punished by being around other people who are really unpleasant … and I think that too is a kind of morality. But it's not a punishment in the way that we generally think of it from fiction of this period."

She introduced a new breed of sassy female protagonist in characters like Elizabeth Bennett and Emma Woodhouse.

"Her heroines are not pictures of perfection," Looser says.

"Their flaws are part of what make them interesting and, arguably, even good."

ALBERT LLOP

Irish author Colm Tóibín, an avowed Austen fan, has found other common themes running through her work.

"She loves a sailor," he says, noting that Austen's youngest brother Charles was a rear-admiral in the navy.

"In Jane Austen, anyone who's in the navy is good, anyone who's in the army is bad, and anyone who has inherited money is suspect."

A real-life marriage plot

Austen never married, but her life wasn't without romance. When she was 20, she formed a brief amorous attachment to Tom Lefroy, a neighbour who was, unfortunately, as impecunious as she, and the match went nowhere.

Then, in 1802, she accepted the proposal of one Harris Bigg-Wither, the brother of a friend, but changed her mind 24 hours later.

Looser says the one-day engagement shows that Austen was ambivalent about the institution of marriage.

Jane Austen's bed at Jane Austen's House Museum in England.

Eurasia Press / Photononstop via AFP

Bigg-Wither appears to have been a somewhat prickly character, but he stood to inherit extensive family estates that would have assured Austen's economic future — no small thing in Regency England.

"It seems likely from what we know of her fiction that she wasn't in love with him," Looser says.

"It would have been a good match. She would have had economic comfort. She would have taken herself off the family balance sheet, so in that sense it would have been a gift to her father and brothers, but she put herself first by taking back her 'yes'."

It's a decision that Looser believes mirrors the fictitious Elizabeth Bennett's refusals of marriage - and one that paid off for Austen.

By the time of her death, the author had achieved a degree of economic independence, earning £700 ($NZ1,617) from her books, a significant sum for the time.

Life beyond death

In a tragic turn of fate, Austen died of an unknown illness when she was just 41.

In addition to her six novels, she left two unfinished fragments, Sanditon and The Watsons.

In the years since her death, her literary reputation has continued to grow to the point where she is now considered one of the giants of the English canon.

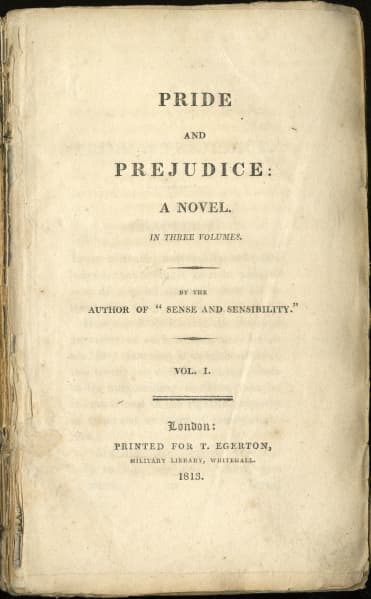

The title page from the first edition of the first volume of Pride and Prejudice, published in 1813.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Her work has provided rich fodder for the screen, too. The first television adaptation of an Austen novel was a BBC production of Pride and Prejudice in 1938.

Many more have followed, including the 1995 six-part series starring Colin Firth in a famously damp shirt as Mr Darcy, and the 2005 film version, which starred a dishevelled Keira Knightley rambling through the muddy English countryside.

While many Austen adaptations are faithful to the period, others — like the inimitable Clueless, a reworking of Emma — have reimagined her work in a contemporary setting.

To Tòibìn — who has taught Austen's novels, including Pride and Prejudice and Mansfield Park, in his creative writing classes at Columbia University — this longevity is no surprise.

"The more you study them and disentangle them, deconstruct them, the more perfect they seem," he says.